So much beauty, so little time

The Great Spangled Fritillary – the male (left) and female.

The lingering days of late summer spell the beginning of the end of the season for butterflies, but some of nature’s loveliest insects will continue to flit about as long as the blossoms linger. Others – namely the Monarch butterfly – might pass over Colorado in the coming weeks in a remarkable migration on delicate wings. The Western Slope is potentially on the route, though I have not seen this spectacle here, ever.

It’s too bad, too, because among butterflies, the Monarch (Danaus plexippus) is one even I can identify. In general, pegging a butterfly by species can be as difficult as differentiating between the plethora of yellow wildflowers around here.

Take the family of fritillaries, for example. There are 14 of the so-called greater fritillaries (the bigger ones) and 16 species of lesser fritillaries (the small ones). Many of them flit about in Colorado. To make it even easier to tell them apart, most of them are predominantly orange. I took a photo of two very different butterflies and sought an expert’s assistance to identify them. Turns out they were both the Great Spangled Fritillary (Argynnis cybele). The male is mostly orange. The female is mostly not.

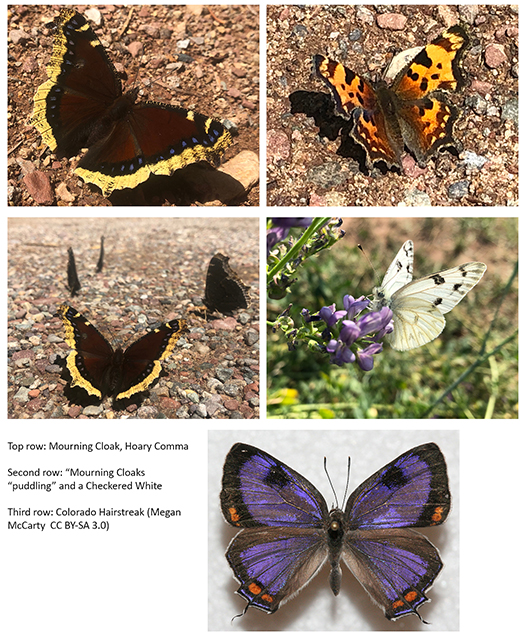

This information piqued my interest in a way that threatens to suck me down a rabbit hole faster than birding or the aforementioned wildflowers. Let the head scratching begin. For starters, why have I never seen a Colorado Hairstreak (Hypaurotis crysalus)? Apparently, this iridescent, purple beauty has been the official state insect since the signing of a bill in 1996. And, it pretty much lives on and around Gambel oak at 6,500 to 9,000 feet. Hello-oo. Next summer, I will be watching, with my soon-to-arrive guidebook in hand.

Meanwhile, I’ve been activity scanning for butterflies as summer wanes ever since the Great Spangled Fritillary caught my eye and expanded my list of recognizable Colorado species to at least two, the other being the Western Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio rutulus). I’ve seen tons of them this summer. Or have I?

I have since learned that the Two-Tailed Swallowtail (Papilio multicaudata) is virtually identical to the Tiger but for … wait for it … two tails. Both species are magnificent, large yellow butterflies with black striping and slender tails hanging from their hind wings. The Tiger has one on each wing; the Two-Tailed has both a long one and a shorter one on each hind wing.

Either way, I haven’t seen either for weeks, though the Two-Tailed variety supposedly remains active into September. Their life cycle ends once adults have mated, eggs have been laid and next summer’s swallowtails are eating voraciously and growing exponentially as caterpillars before moving into the chrysalis stage to overwinter. New adult butterflies will emerge in the spring. It’s the process of metamorphosis.

Some butterflies actually hibernate in their adult form in a sheltered spot. Mourning cloaks, dispersed throughout Colorado and very common locally, do this. Adult butterflies that don’t migrate, or hibernate, will perish when their food sources wither and temperatures drop, but early fall around here is still a good time to watch for the Common Checkered Skipper and Western Branded Skipper, Mourning Cloak, the Viceroy, Orange Sulphur (one of the most common butterflies in the country), the Hoary Comma and Two-Tailed Swallowtail, among others, I’m told.

Various fritillaries are also still about. I’ve noticed members of this confounding group on thistle blossoms – among the late-season favorites for adults, though they are dependent upon violets in their caterpillar stage. The caterpillars hatch in the fall and go to sleep right away without feeding, according to the U.S. Forest Service. They awaken in spring as violets begin to grow. The timing is key to their survival.

Cabbage butterflies are everywhere. Also called the Cabbage White (Pieris rapae), it’s not native, but is the bane of many a vegetable gardener. In its caterpillar stage, it’s particularly fond of cruciferous vegetables – my broccoli plants to name one. The adults don’t harm plants, but the females lay eggs in the crops.

The Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui), another common butterfly in these parts, also migrates, taking several generations to complete the process. The extraordinary southward migration by the Monarch however, is the longest of any single butterfly.

Most adult Monarchs live two to five weeks; it’s the migratory generation that may live up to nine months, mating the following spring. It takes successive generations to complete the northward journey.

Butterflies demand notice, but not just for their dazzling wing designs. Adult butterflies fluttering among the flowers next to a trail or in a garden may only live a week or two at best. In that span they must mate and females must lay eggs. It’s worth stopping to notice them.

A BIT ABOUT BUTTERFLIES

- Monarchs west of the Rockies migrate to central and southern California, while the eastern population makes the flight to Mexico. Some of them start in southern Canada! Sadly, the monarch population has declined by about 90 percent since the 1990s, according to the National Wildlife Federation.

- One of the easiest ways to tell the difference between a butterfly and a moth is to look at the antennae. A butterfly’s antennae are club-shaped with a long shaft and a bulb at the end. A moth’s antennae are feathery or saw-edged. Also, butterflies tend to fold their wings vertically up over their backs. Moths tend to hold their wings in a tent-like fashion that hides the abdomen.

- The fastest butterflies are the skippers, which can fly 37 mph (about as fast as a horse can run). Most butterflies hit speeds of 5 to 12 mph in flight.

- If you see butterflies gathered to drink from a mud puddle – called puddling – they are likely males taking in salts and other minerals not found in flowers, to aid in reproduction.

- Butterfly and moth sightings are tracked at butterfliesandmoths.org – check out the Pitkin County list.

- The iridescent quality of butterfly wings results from light passing through a transparent, multi-layered surface of tiny scales. It’s reflected more than once; the multiple reflections compound one another.

- In general, the colorful top layer of a butterfly’s wings is used to attract a mate; the lower surface, which shows when the wings are closed, helps them hide from predators or sends a message to predators that eating them would be toxic.

- The study of butterflies is lepidoptery, a branch of entomology. An expert in butterflies is a lepidopterist.

- Collect butterflies with your cell phone camera and study them with binoculars. No need to net them and mount them behind glass, given the population declines in some species.

- Plant to attract butterflies. Online advice abounds!

Janet Urquhart is Planning and Outreach Specialist for Pitkin County Open Space and Trails. (She is not a lepidopterist.)