Wolves on open space? It’s likely

A gray wolf in the snow. Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

They’re here.

Ten newly reintroduced gray wolves are on the ground in Colorado and up to five more are expected to be released by mid-March. With a reintroduction goal of 30 to 50 wolves within three to five years, according to Colorado Parks and Wildlife, it’s likely that Pitkin County will see gray wolves wandering its landscape for the first time in eight or so decades.

Will they show up on open space? Count on it, according to Jonathan Lowsky, wildlife biologist with Basalt-based Colorado Wildlife Science.

“They’re going to be here. People in the Roaring Fork Valley are going to hear wolves howl,” said Lowsky, who conducts wildlife surveys on Pitkin County open spaces in consultation with Pitkin County Open Space and Trails.

Wolves are mobile, covering as many as 30 miles a day to hunt, and a pack’s territory can be 20 to 120 square miles, according to Colorado Parks and Wildlife. While CPW labels wolves as “habitat generalists,” they’re commonly found in areas with plentiful deer and elk populations. The Roaring Fork Valley, and county open spaces, fit that bill, Lowsky said.

Area open spaces and the White River National Forest are already home to a couple of large predators, namely mountain lions and bears, which prey upon deer and elk. Lions tend to be particularly secretive and nocturnal, and both animals generally shy away from people. Among the thousands of users at Sky Mountain Park during the summer season, few can claim to have seen one of the park’s lions, though wildlife cameras confirm their presence.

Living with wolves

Wolves, too, are calm and elusive, according to Colorado Parks and Wildlife, which has produced a brochure, Living with Wolves – How to Avoid Wildlife Conflicts, to help Coloradans share the landscape with a species that once made its home here and now, does again.

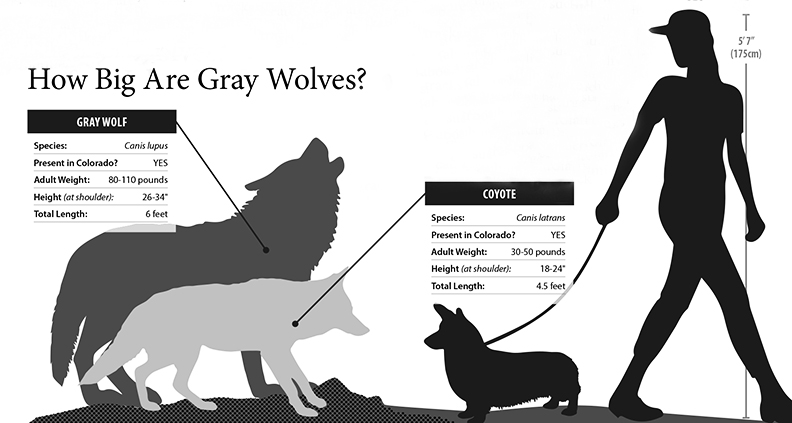

It is rare for wolves to pose a direct threat to humans, according CPW, but the brochure offers a range of information on living and playing in wolf country, what to do during a wolf encounter, how to recognize a wolf (versus a coyote, for example), and much more.

A 2021 report by a Norwegian institute that tallied wolf attacks on humans worldwide in 2002 through 2020 put the danger posed by wolves this way: “…the risks associated with a wolf attack are above zero, but far too low to calculate.”

The report found evidence of 12 wolf attacks involving 14 victims in Europe and North America during the 18-year span; two (one in Alaska and one in Canada) were fatal. To put those events in context, there are close to 60,000 wolves in North America and 15,000 in Europe, all sharing space with hundreds of millions of people, the report noted.

Management of county open spaces in the near term will acknowledge the potential for wolves and provide guidance to the public as warranted, according to Liza Mitchell, natural resource planner and ecologist for Open Space and Trails. A draft management plan update for Filoha Meadows Nature Preserve, currently in the works, will be the first such plan to include a provision regarding wolves. It will call for keeping abreast of the CPW reintroduction process, coordinating with CPW as needed and providing guidance and education to the public in the event of actual wolf presence at Filoha.

Filoha Meadows in the Crystal Valley is a lightly visited open space that borders the White River National Forest. Closed to human use for 9 months each year and heavily used by elk in winter and spring, it’s a likely spot for wolves to at least pass through, according to Lowsky. Wildlife cameras on the property could confirm a wolf presence, though the meadows are also readily viewable from Hwy. 133.

“With wolves on the ground now, it is important to move beyond ideological or political conversation and toward acceptance, curiosity and patience,” said OST’s Mitchell. “Nature, and humans, adapt over time and while I expect there will be both amazing and difficult moments in this process for all, our goal at Open Space and Trails continues to be to provide space for flora and fauna to survive, thrive and adapt to our ever-changing world, and to foster human enjoyment of nature without detriment to the ecosystem.”

What about livestock?

In addition to habitat value and recreational opportunities, county open spaces sometimes contain an agricultural component. Among the 790 acres of open space currently leased for agricultural use, there are a few livestock operations. CPW has provided a great deal of information and access to resources for Colorado ranchers, including a Resource Guide to Reduce Depredations.

In Pitkin County, Open Space Agriculture Specialist Drew Walters is reaching out to open space lessees to offer information and put producers in touch with resources as needed.

“Wolves will be in this area at some point. It’s kind of a matter of time,” Walters reasoned. Now is the time for agricultural producers to start keeping records (if they don’t already) that could assist them in getting expanded forms of compensation for losses other than the actual depredation of an animal. With adequate record keeping, a producer may be compensated if wolf-caused stress results in decreased weight gain or reproduction among sheep or cattle, for example, according to Walters.

“I’d say that’s how producers in the area can really start prepping this year,” he said.

Incidentally, Walters and CSU Extension services in Eagle and Garfield counties have Redbooks (livestock record-keeping books) available.

Alyssa Barsanti, owner of Marigold Livestock Co., raises sheep on Glassier Open Space and plans to expand her herd. In addition, she has purchased 10 steers that will graze at Glassier this year. She admitted the prospect of another predator on the landscape makes her “a little uneasy,” but she has successfully defended her flock thus far with electric fencing, a regular presence on the property, keeping the lambing area near residential buildings, and the addition of guard dog Levi.

She previously had lambs at Emma Open Space and lost two to predators before Levi entered the picture.

“I only had seven at the time so that was a really big hit,” Barsanti said. “I haven’t lost a single animal to predation since I got him. His bark is tremendous.”

Glassier is home to mountain lions, bears, bobcats, coyotes, foxes, raccoons and weasels, but Barsanti has successfully reared meat chickens on the property along with sheep. Unlike some ranchers, though, she does not graze livestock on vast federal lands where the danger posed by predators is likely greater.

Recognizing the wolf’s historic place in Colorado, Barsanti said she’s accepting their return despite some apprehension.

“There are parts of it that I find really exciting. I think it’s really cool and really powerful for the ecosystem and the landscape,” she said. “There’s a lot that we don’t know yet. I think it’s going to be a learning curve. I think it will be hard, but I’m ready for that. I’m eager to see how it plays out.”

Barsanti’s mindset is one all Coloradans might embrace, said Open Space’s Mitchell.

“Humans have co-existed with wolves for a very long time, with various ups and downs,” Mitchell said. “We can learn and adapt if we choose to. Let’s choose to.”

– By Pitkin County Open Space and Trails

KEY LINKS

CPW: Living With Wolves – How to Avoid Conflicts

Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan

CPW: Resource Guide to Reduce Depredations

Video: Dec. 8 release of 5 wolves in Grand County, CO

CPW: Stay Informed – Wolf Updates

Source: Colorado Parks and Wildlife

Levi protecting the Merigold sheep in 2021.