From past to present on Smuggler Mountain

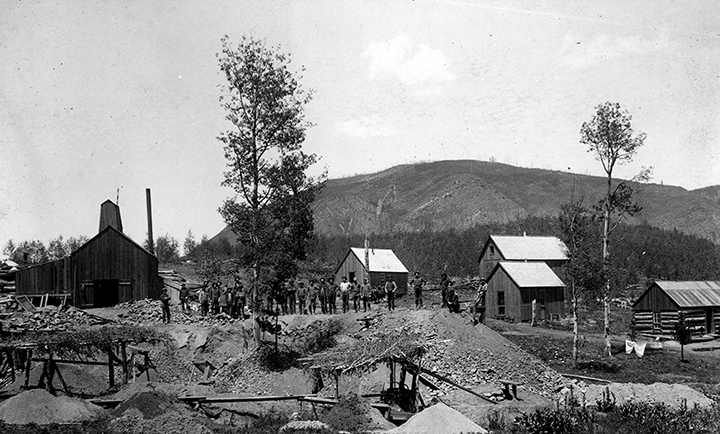

The Park-Regent Mine on what is now Smuggler Mountain Open Space, with Red Mountain visible in the background. (History Colorado. Accession #83.130.14)

Note: This history of Smuggler Mountain Open Space will be part of a 2024 updated management plan for the open space. The draft plan will be open to public comment in the fall. Keep tabs on this planning effort.

The story of Smuggler Mountain parallels the story of Aspen.

Once part of a pristine landscape where the nomadic Ute People wandered for more than 800 years, the mountain was ravaged by the industrial frenzy that ensued shortly after the first prospectors arrived at the foot of Aspen Mountain in 1879.

Scarcely more than a decade later, Smuggler, and Aspen, would fall into quiet years of near abandonment and decay. Many of the great mine workings dotting Smuggler Mountain and elsewhere stood silent. Huge piles of mine waste at the base of the mountain and fanning out on its flanks dominated an otherwise denuded landscape.

The force of nature and the hand of man both played a role in the mountain’s gradual reclamation, though telltale tailings piles and other evidence of Smuggler’s former mining prominence remain. The legendary Smuggler Mine itself, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, sits at the base of the mountain.

Today, Smuggler Mountain is both wildlife habitat and recreational playground. Visitors and residents alike seek out Smuggler Mountain Open Space, 300 acres largely bounded by the White River National Forest and easily accessed directly from Aspen. That the open space is a place of trails and forest rather than homes and roads is a testament to the community’s passion for the place and, ironically, one man’s desire to develop it.

In the beginning…

Smuggler Mountain is but a dot in a vast landscape where the native Utes wandered for centuries, though little physical evidence or documentation of their presence in the upper Roaring Fork Valley exists. By the time the first prospectors made their way from Leadville to what would become Aspen, the Utes were already being forced off the lands of western Colorado that had been ceded to them by treaty.

Historians generally believe the Utes hunted in the upper Roaring Fork Valley in summers, and camped at Ute Springs, near present-day Glory Hole Park in Aspen.[1] Early settlers were familiar with former native campsites that showed wear and tear from long use – the meadows at Ute Springs among them.[2] According to the Southern Ute tribe, however, no oral history of Utes in the Aspen area exists.[3]

The Colorado Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation has logged 50 known cultural sites within 12.5 miles of Aspen, but most are unassociated with native inhabitants and only two are arrow points of the type made by Utes.[4] Various historical sites are documented, including buildings and ruins.

In an area encompassing most of Smuggler Mountain Open Space, seven historical sites have been recorded, but none involve Native American artifacts. Of 13 sites in the lower section of the Hunter Creek Valley, one has native connections, though it is not known whether it is Ute in origin.[5]

It is highly probable, however, that the Ute People wandered the length of the Roaring Fork Valley and were familiar with the places that became Smuggler Mountain and Aspen. There is no question about the activities that occurred once prospectors and investors established Ute City, as Aspen was initially known.

Mining: The boom and bust

Miners extracted primarily silver, lead and zinc from Smuggler Mountain, driving tunnels thousands of feet below the surface. Massive amounts of timber were required to support the mines and other construction, leaving Smuggler and other area mountainsides largely denuded. The behemoth Smuggler Mine was a large industrial complex. Located at the base of Smuggler Mountain Road and still in existence today (minus most of the buildings that once served the undertaking), the privately owned mine marks the start of the ascent up the road for the hundreds of people who bike and hike it daily. Higher up, the Iowa Shaft, Bushwacker and Park-Regent mines were situated on what is now open space.

Smuggler’s Della S claim, also part of the open space, was frequently in the news as the mining camp’s newspapers played up developments at the area’s many diggings. In 1892, for example, the Aspen Daily Chronicle reported a strike of exceedingly rich ore at the Della S, featuring “large flakes of pure silver and chunks of native.” (Native silver is uncombined with other elements.)

The Hunter Creek Cutoff Road, passing next to the Iowa Shaft mine, is partially constructed of rock waste from mining. It follows the top of a dam that diverted water running down the mountainside away from mine activity and may have captured water for mine use.[6]

A visible washout on the face of the mountain is also left from Aspen’s mining era. Slicing through a segment of Smuggler Mountain Open Space above Hunter Creek, this scar resulted from water overflowing a flume that once carried Hunter Creek water to a power plant for the generation of electricity.[7] The flume was under construction in 1886 and clearly visible from Aspen.[8]

The demonetization of silver in the first half of the 1890s resulted in an economic crash for Aspen. A few mines carried on in fits and starts, but operations and output slowed considerably and much of the town’s populace departed. The goings-on on Smuggler Mountain largely ceased to be newsworthy until the 1960s, when McCulloch Oil Co. renewed milling and mining operations on the mountain.[9]

Aspen’s slow, decades-long rebound from mining town to year-round resort saw the collapse and dismantling of many of the mine works on Smuggler and elsewhere. Abandoned mine tunnels caved in or filled with water and tailings piles were smoothed over or simply left to settle into the landscape. Old cables, pipes and machinery rusted in place, or were scavenged as scrap, along with wood used in building construction. Forests regenerated.

Smuggler Mountain Road and the Cutoff Road into the Hunter Creek Valley saw use by Jeeps and motorbikes, but not much else.

Youngsters on BMX bikes rode on the mine dumps at the base of Smuggler. Those lucky enough to own a minibike (an off-road, motorized bike that was smaller than a motorbike) found plenty of playgrounds, including a well-established, user-created track on a flat bench within what is now Smuggler Mountain Open Space, above the Overlook platform.

Lorenzo Semple, a pre-teen in Aspen in the 1970s, remembers only four-wheel-drive Jeeps, motorbikes and minibikes using Smuggler Mountain. It was not a favored hike and no one wanted to pedal up the rough road. Some drove up for the purpose of hunting or fishing at Warren Lakes high on the mountain.

“The concept of someone pedaling a bicycle up Smuggler was so foreign that no one even gave it utterance,” Semple said.[10]

Existing 4-wheel roads began seeing mountain bike use as the sport gained traction in the 1980s because there were few other places to ride. The 1980s also brought another facet of the long-neglected mountain into the spotlight – its real estate.

One man’s battle

George “Wilk” Wilkinson moved to Aspen sometime after first visiting the resort as a ski racer in international competition in 1960 and remained a full-time resident until 1995. Despite a diverse range of talents, from ski racing to filmmaking and photography, his Aspen legacy is inextricably linked to Smuggler Mountain.[11]

Through painstaking title work in the early 1980s to track down the owners of an assortment of mining claims on Smuggler, Wilkinson assembled about 220 acres (34 patented mining claims) as his own – the bulk of it a contiguous, mid-mountain piece above Smuggler Mountain Road, beyond the Overlook platform.[12]

What the public had come to think of as public open space was most certainly not. The simple, wooden deck that materialized at the Overlook was actually on private property. Elsewhere, the popular minibike track was largely on Wilkinson’s land, until he used heavy equipment to destroy the attraction, according to Semple.

The mountain’s long-forgotten squabbles over mineral deposits gave way to a modern fight – development versus conservation. The community’s fondness for Smuggler and the desire to conserve it was one impetus for the formation of the county open space program in 1990. That mindset, however, ran counter to Wilkinson’s vision for his landholdings, triggering a tug-of-war with the county that consumed more than a decade.

Pitkin County, the City of Aspen and Aspen Valley Land Trust had slowly begun conserving pieces on the face of Smuggler as early as 1974, through donations, purchases and other mechanisms. A key acquisition came in 2000 with the proposed transfer of the 10-acre B&M Lode mining claim – site of the popular Smuggler Overlook platform – to the county. The deal was completed in 2005, though volunteers replaced the old platform with a new one in 2003.

Wilkinson, however, resisted open space overtures, even though his development applications went nowhere. Increasingly frustrated, Wilkinson contended the county was conspiring to stymie the development of Smuggler, even changing its land-use regulations to thwart his efforts. While the county conceded he had development rights, the two sides were miles apart on how many, with Wilkinson at one point proposing 86 units on his property. His land-use battles frequently spilled into the courtroom. At one point, in suing the county for $159 million, Wilkinson also claimed his property was a “foreign state,” essentially seceding from Pitkin County.[13]

The feud escalated in the early 1990s, when Wilkinson constructed a substantial residence on his property. He had obtained a permit exemption for a single-story agricultural structure without water or electricity, but built a home that was partially two stories, and had electrical outlets and water piped from a stream running through his land.[14] When settlement negotiations fizzled, the county ordered the structure’s demolition. A county crew put most of Wilkinson’s belongings in storage, and the county continued to pay the storage fees for years, recalled then-County Manager Reid Haughey.[15]

Wilkinson apparently returned to residing on his land, joined by others. In the late 1990s, the county worked to evict renters living in makeshift structures and vehicles on his property, as well as in vehicles in the parking lot at the base of the mountain, over which Wilkinson claimed ownership. Wilkinson said he was providing affordable housing; the county alluded to fire danger and other safety and sanitary concerns arising from the tepees and other unpermitted residences on the mountain.[16] In 2001, a man died from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning in the propane-heated bus he called home on Smuggler. In 2002, a squatter’s camp along the road on county land was dismantled by a county crew. A vehicle, dilapidated camper and an outdoor deck replete with furniture were hauled away.

Ownership of the Smuggler base-area parking lot was not the only bone of contention in the county’s ongoing battle with Wilkinson. In December 2000, Wilkinson ordered the county’s Community Development director off the Hunter Creek Cutoff Road, claiming the road was private where it crossed through his property. Wilkinson had made similar claims about ownership of Smuggler Mountain Road on his property, as well, and the two sides were already in court over that issue. The Cutoff Road was added to the judicial review. The county ultimately prevailed.

In 2003, the Aspen City Council directed the city attorney to negotiate with Wilkinson for a potential open space purchase. City voters had approved an open space tax in November 2000 with Smuggler on their minds. Experts spent two years assessing Wilkinson’s holdings, coming up with an $8.1 million appraisal as a starting point. A $10 million offer was rejected, so the city offered $12 million. Wilkinson turned it down, countering with a complex proposal that the city attorney said he quit trying to figure out when the first two numbers in Wilkinson’s pitch added up to $21 million.[17]

Then, in August 2005, Wilkinson listed his property for sale for $15 million. By then, his landholdings totaled 170 acres. That November, the county put the land under contract with the city committed to paying half of the sum. At the time, it set a record price for an open space acquisition. A handful of smaller acquisitions on Smuggler followed, including the purchase of mineral rights, ensuring mining activity would be relegated to the mountain’s past.

Wilkinson had been diagnosed with brain cancer in April 2005 and died in September 2006.[18] The following summer, about two dozen friends and relatives gathered in a clearing on the Smuggler mountainside in remembrance. A stone, carved with part of a poem he wrote, memorializes the spot. Though the etching has faded with time, it is still possible to read the inscription: “The dance of life touches those who participate in passion…” Loved ones scattered Wilkinson’s ashes over the land he wound up playing a key role in conserving.[19]

Transforming a landscape

The purchase of Wilkinson’s land necessitated a massive cleanup. His compound was closed to the public while old mines were secured (one mine opening was covered by a trash can lid) and truckloads of accumulated materials were hauled from the site. Large trucks and heavy machinery rumbled up and down Smuggler Mountain Road throughout late summer, 2006.[20]

Items that had to be cleared from the landscape included large buses that had been turned into residences, a mobile home, and huge volumes of wood and scrap metal, including drilling equipment dating back to the 19th century. The remains of the house that had been demolished were still there, as was a large assortment of vehicles – some fairly new, some ancient and rusting. There were shipping containers crammed with items.[21] The cleanup cost some $60,000.[22]

Once the land was cleared, a 6-year effort to reclaim the landscape commenced, involving the city, county and community volunteers who helped transform the open space through a series of Roaring Fork Outdoor Volunteer projects. Old roads were converted to singletrack trails and new trails were constructed, picnic tables were installed and fencing was erected to protect areas from further damage, leaving Smuggler Mountain Road as the only vehicular route through the open space. Three mine sites – the Bushwacker, Iowa Shaft and Park-Regent – were established as historical sites with interpretive signs to give visitors insight into the mountain’s past use.

Damaged areas were reseeded in the summer of 2012. That September, the reclamation effort was deemed complete and nature was allowed to finish the work. Today, many users likely can’t tell that the grasses flanking the singletrack trails in spots represent a real restoration success.

– By Pitkin County Open Space and Trails

[1] Ute People Pre-1879, Aspen Historical Society, aspenhistory.org/aspen-history/the-utes-pre-1879/

[2] “Roaring Fork Valley – An account of its settlement and development,” Len Shoemaker, Sage Books, Denver CO, p17.

[3] “The Utes and Aspen – More unknown that known,” Tim Willoughby, The Aspen Times, May 21, 2023, p3.

[4] “The Utes and Aspen – More unknown that known,” Tim Willoughby, The Aspen Times, May 20, 2023, p3.

[5] Jason LaBelle, Colorado State University, via email, Feb. 1, 2024.

[6] “Signs of the past on Aspen’s Smuggler Mountain,” Janet Urquhart, The Aspen Times, Nov. 4, 2012, p1.

[7] “The Story of Aspen,” Mary Eshbaugh Hayes, Aspen Three Publishing, Aspen CO, p29.

[8] “Light and water,” Rocky Mountain Sun, May 22, 1886, p2.

[9] Smuggler begins silver shipments,” The Aspen Times, Sept. 15, 1966, p13b

[10] Lorenzo Semple, telephone interview, Feb. 23, 2024.

[11] “’Wilk’ dies at 63, leaves Smuggler legacy,” Scott Condon, The Aspen Times, Sept. 27, 2006, p1.

[12] “County wins Smuggler battle, war continues,” Scott Condon, The Aspen Times, Feb. 1, 1994, p1.

[13] “Wilk: Don’t tread on me,” Scott Condon, The Aspen Times, Oct. 3, 1994. p1

[14] “County wants Wilkinson’s buildings torn down,” Michael Bourne, Aspen Daily News, Oct. 9, 1990, p1.

[15] Reid Haughey, telephone interview, April 25, 2023.

[16] “Body found on Smuggler,” Aspen Daily News, Feb. 7, 2001, p3.

[17] “City gives up on Smuggler,” Janet Urquhart, The Aspen Times, June 29, 2004, p1.

[18] “’Wilk’ dies at 63, leaves Smuggler legacy,” Scott Condon, The Aspen Times, Sept. 27, 2006, p1.

[19] “Wilk memorialized on Smuggler,” Janet Urquhart, The Aspen Times, June 15, 2007. p1.

[20] “What Wilk left behind: Massive cleanup under way on Smuggler,” Chad Abrahams, The Aspen Times, July 28, 2006, p1.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Gary Tennenbaum, Pitkin County Open Space and Trails director, February 2024.