Soil moisture monitors reveals unseen story

An iRON soil moisture monitor on Independence Pass. (Karin Teague photo)

While this winter’s snowpack, or relative lack thereof, garners all the headlines, the depth of the snow is only half of the story when it comes to water availability in 2021. What’s beneath the ground’s surface, hidden from view, will play an important role in everything from how much water winds up in rivers and reservoirs, to how the wildfire season shapes up.

Soil moisture levels – established last fall before the ground froze – are a key component of spring runoff. The wetter the soil, the less melting snow it will absorb before the ground is fully saturated and the water starts flowing. So how wet was the soil last fall? Not very.

The Aspen Global Change Institute’s interactive Roaring Fork Observation Network, or iRON, tracks soil moisture at 10 stations in the Roaring Fork Valley. They’re placed at locales ranging from the alpine environment of Independence Pass to sites of decreasing elevation and differing ecosystems between Aspen and Glenwood Springs. Seven stations are located on Pitkin County open space properties, including the Orphant Boy mining claim on the Pass, Smuggler Mountain Open Space, North Star Nature Preserve (two sites), Sky Mountain Park (two sites) and Glassier Open Space. (Orphant, incidentally, is the correct spelling of the mining claim; it’s an obsolete spelling of orphan).

Devices at each station measure soil moisture at depths of 2, 8 and 20 inches. The data from iRON’s debut station, at Sky Mountain Park, goes back to mid-2012, when it was installed. Additional stations followed. Throughout the life of the program, the spring snowmelt has always been sufficient to saturate the soils to the 20-inch depth at the expanding array of stations, according to Elise Osenga, AGCI’s community science manager.

Snowpack is critical to saturate the soil at 20 inches; only a prolonged or heavy rain event during the summer will nudge up the moisture level at that depth. Once the soil hits saturation, usually in spring, the drying out of the soil depends on the disappearance of the snowpack, and then precipitation. Moist soil in early summer can help reduce wildfire danger until the summer rains begin – if they begin. They didn’t in 2020.

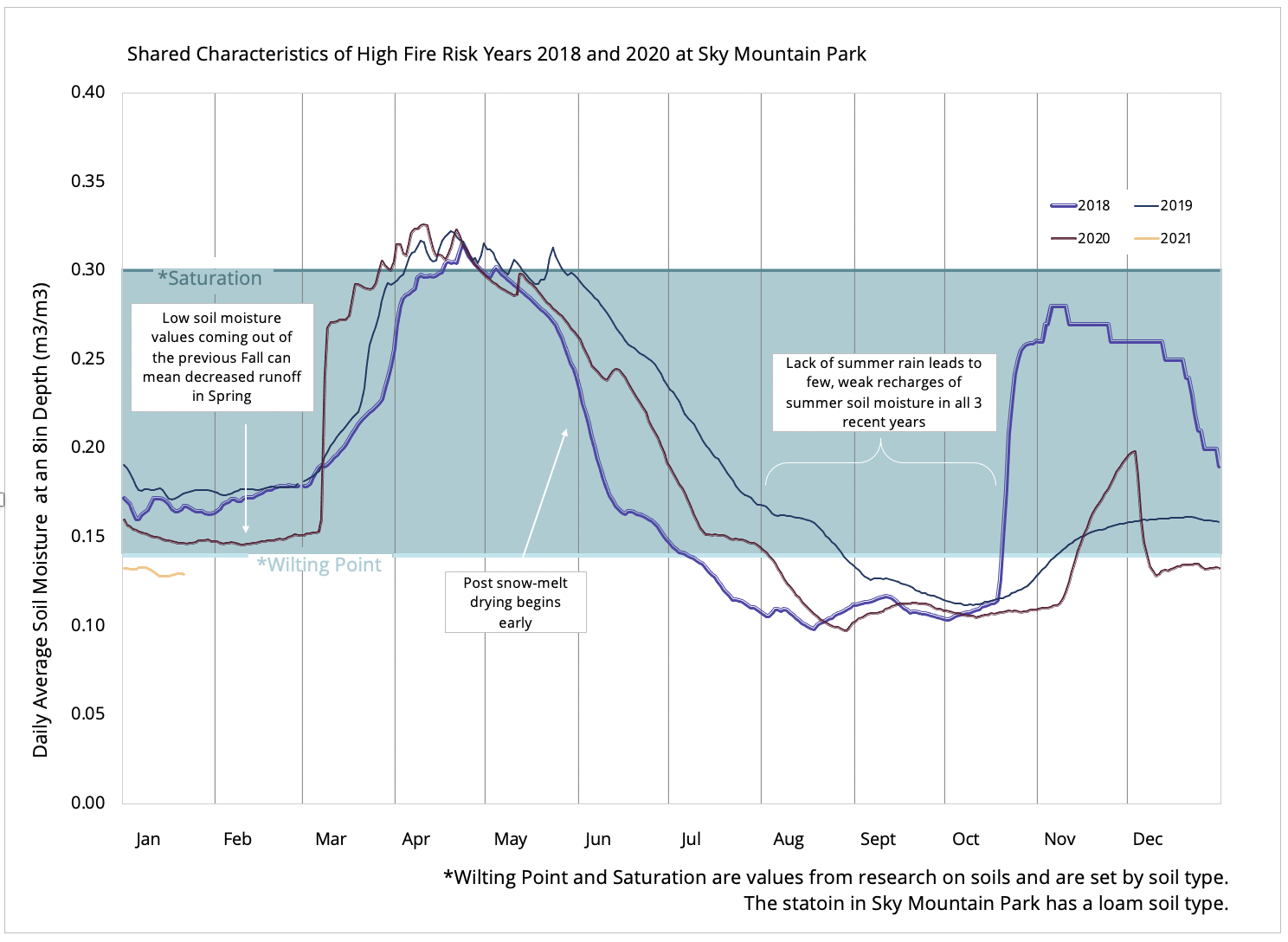

A look at just one set of data – at the 8-inch depth atop Sky Mountain Park – validates soil moisture as an indicator of things to come (see graph below). Why 8 inches? Moisture at that depth isn’t impacted by small rain events, but is an indicator of seasonal changes and moderate rain events.

In 2018 (year of the Lake Christine Fire on Basalt Mountain), moisture hit 14 percent on July 8. Fourteen percent is the wilting point, when many plants have a difficult time extracting moisture, in the loam-type soil present at the Sky Mountain Park monitoring site.

In 2019, a quiet year in terms of wildfire statewide, moisture at the Sky Mountain site didn’t hit 14 percent until Aug. 29. In 2020, soil moisture dropped to the wilting point on Aug. 4 – a relatively late date despite a very dry summer. The Grizzly Creek Fire in Glenwood Canyon, incidentally, began Aug. 10, 2020.

On Dec. 31, 2020, soil moisture at the 8-inch depth at the Sky Mountain Park station measured 13 percent – the lowest reading at year’s end in that spot since iRON recordkeeping began. It will be the starting point when snowmelt begins this spring.

Interestingly, iRON has only known drought. Colorado is within a region that has been in a prolonged drought since before the monitoring network was installed. “We’re looking at really dry years within a dry time already,” Osenga noted.

One can only speculate about what the network’s jagged graphs would look like in a non-drought conditions.

In the meantime, water managers across the state are already planning a course of action in 2021 based on such factors as snowpack and rainfall projections on a watershed-wide basis. It is the AGCI’s hope that soil moisture data will eventually be an important component in those calculations. Drought or not, the more information, the better.

“If you have the data, it gives you a chance to adapt accordingly,” Osenga said.

– By Pitkin County Open Space and Trails

FIND OUT MORE

Aspen Global Change Institute’s interactive Roaring Fork Observation Network

Welcoming in the new (water) year from the ground on down, Oct 2018